A revolutionary idea of abolishing LGU system (from governors, mayors to barangay captains) and changing the 80-member regional representation to what I call the “Autonomous Regional Parliament of the Bangsa Assemblies (ARPBA)” as the new name of BARMM. It shall be composed of 261 elected officers and service-based sectoral representatives of the nine standalone Bangsa Assemblies referring to (1) The Bangsa M’ranaw Assembly, (2) The Bangsa Magindanaw Assembly, (3) The Bangsa Sug Assembly, (4) The Bangsa Iranun Assembly, (5) The Bangsa Sama Assembly, (6) The Bangsa Yakan Assembly, (7) The Bangsa Bajaw Assembly, (8) The Bangsa Indigenous Peoples Assembly, and (9) The Bangsa Settler Communities Assembly.

The number of representatives per Bangsa Assembly is determined by proportional representation based on the number of registered community welfare clans and societal sectors representation. A community welfare clan is usually composed of a group of close-knit and interrelated families and subclans while societal sectors refer to regular service-oriented representations. This type of non-territorial and culturally embedded representation will control and limit the influence of prolonged political dynasties established by a handful kinship of political elites. All community welfare clans and communal service-oriented sectors will have equal political representation and equitable access to governmental public resources. It will no longer be accessible to very few clans/families who have been holding the positions of governors, mayors, or barangay captains for quite some time and yet for decades there are minimal economic progress with poor quality of basic services (e.g., electricity, water, internet/mobile connectivity, road infrastructure, etc.) delivered.

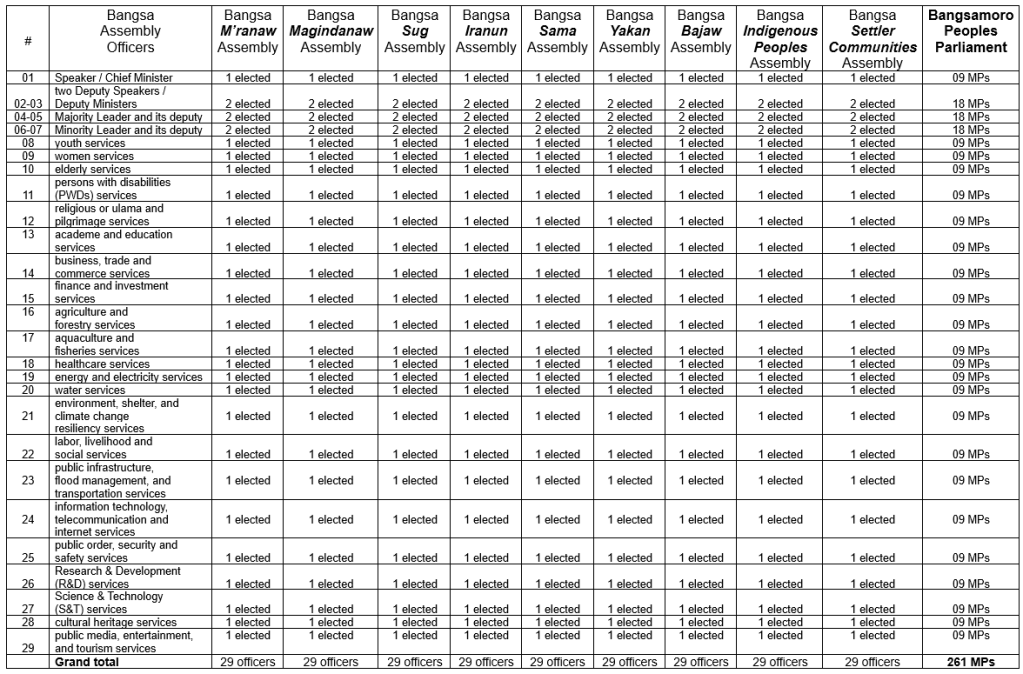

Upon determining Assembly representations, each Bangsa Assembly shall elect their own (1) Speaker who shall take the Chief Minister position, (2-3) two Deputy Speakers who automatically becomes the Deputy Ministers, (4-5) Majority Leader and its deputy, (6-7) Minority Leader and its deputy, and regular service-based sectoral representatives from the (8) youth services, (9) women services, (10) elderly services, (11) persons with disabilities (PWDs) services, (12) religious or ulama and pilgrimage services, (13) academe and education services, (14) business, trade and commerce services, (15) finance and investment services, (16) agriculture and forestry services, (17) aquaculture and fisheries services, (18) healthcare services, (19) energy and electricity services, (20) water services, (21) environment, shelter, and climate change resiliency services, (22) labor, livelihood and social services, (23) public infrastructure, flood management, and transportation services, (24) information technology, telecommunication and internet services, (25) public order, security and safety services, (26) Research & Development (R&D) services, (27) Science & Technology (S&T) services, (28) cultural heritage services, and (29) public media, entertainment, and tourism services.

The elected sectoral service representatives shall automatically take the leadership role of their respective ministries, agencies and offices (MOAs) within a particular Bangsa Assembly, thus public services are devolved and trickle down to their own people. It is up to the particular Bangsa Assembly’s preference if they wanted to add other types of services in the budget appropriation in creating new public service-oriented MOAs. For now, each Bangsa Assembly shall have a total of 29 elected Assembly Officers which shall form part the total number of Members of the Bangsamoro Peoples Parliament at the regional level, i.e., a total of 261 MPs. The computation is shown below:

The eligible candidates for BPP Speakership are the nine Speakers of the nine Bangsa Assemblies. All 261 MPs will have to vote to determine the regional BPP Speaker. This same method shall also be applied to determine the two regional BPP Deputy Speakers, one regional BPP Majority Leader and its deputy, and one regional BPP Minority Leader and its deputy. The regional service-oriented sectoral representations shall form their own “BPP Caucus” which shall proactively initiate the crafting of legislations reflective of the voice and interest of the sector their representing. For example, the nine MPs under the women services of the Bangsa Assemblies shall create the “BPP Women Caucus” which shall spearhead GAD-relevant advocacies in legislating laws and implementing public policies both in their particular Bangsa Assembly’s homeland and in the regional Bangsamoro Peoples Parliament of BARMM.

You must be logged in to post a comment.